Dabbling into CTFs: Cracking "Some Assembly Required 4" from the picoGym

Recently, I’ve been getting into CTFs. I’ve been delving into the picoGym - the archived challenges from previous iterations of PicoCTF. Since I’m new to this whole capture-the-flag thing, I’m not that good at it (yet) - occasionally, if the problem is really above my head, I give up and look up some write-up someone posted online (looking at you, LiveArt).

Yesterday, I managed to crack a challenge named “Some Assembly Required 4” that I thought was pretty difficult. So let me explain the way I solved it:

The Problem - Some Assembly Required 4

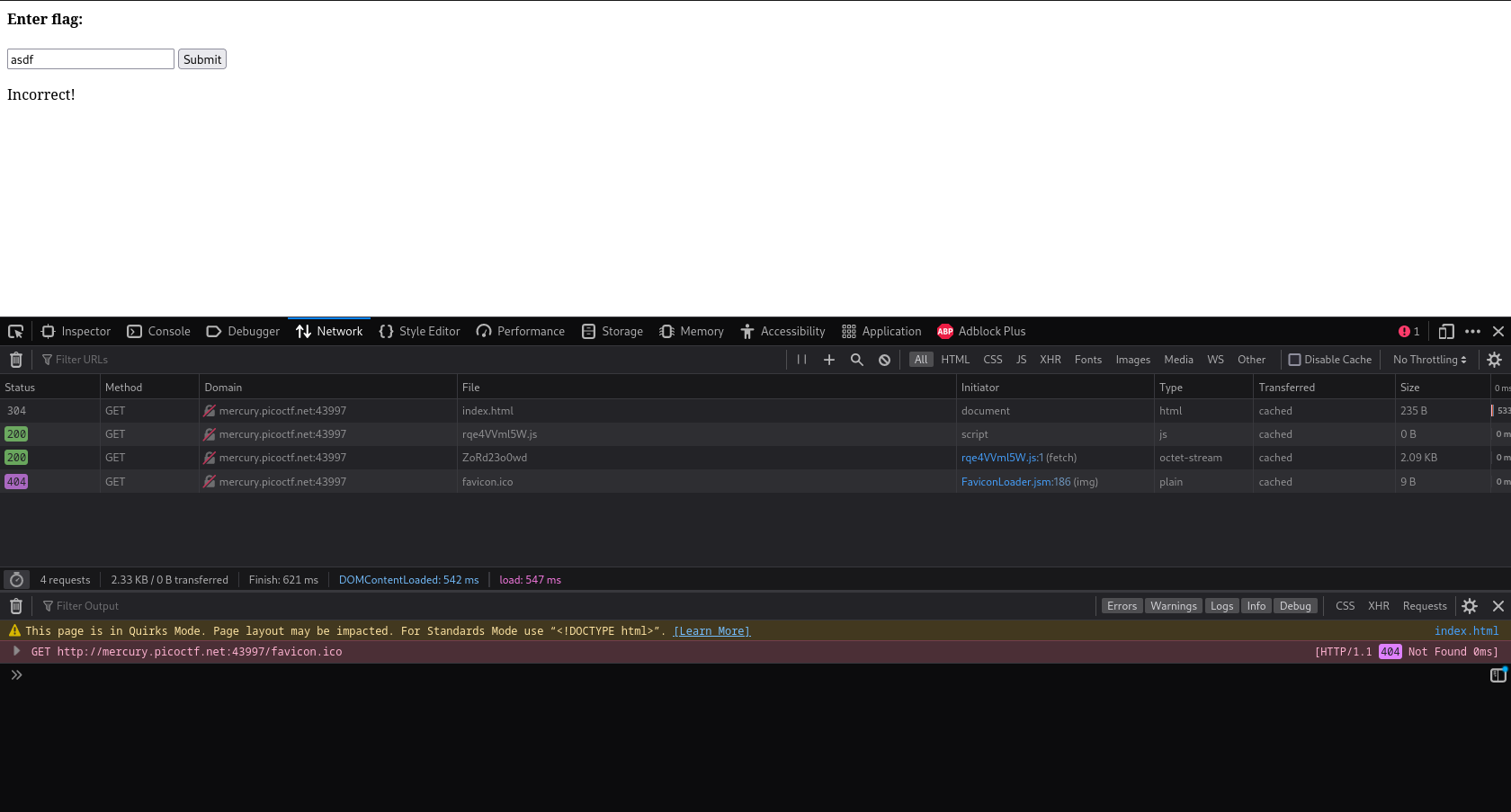

In this challenge, we are presented with a single webpage. This webpage contains a textbox and a submission button. After playing around with it for a bit, we find that the form checks whether or not the text we put in is the flag’s value, and tells us if it is correct/incorrect. Upon loading the network tab of devtools, it’s apparent that all this flag-checking is done locally - there’s no network requests being sent whenever we click on the “Submit” button:

Inspecting the JS

With this in mind, the next logical step is to look at the source code, particular the JS file which must be holding this flag-checking method. It’s minified, and even after pretty-printing it’s still very obfuscated:

const _0x2f65 = [

'instance',

'93703gBAUAn',

'442816lLbold',

'instantiate',

'1ZFMVDM',

'381193zsgNYQ',

'check_flag',

'result',

'length',

'48829pZIrMh',

'648920pjyJsd',

'copy_char',

'21760lQoqpJ',

'arrayBuffer',

'1zBwHgR',

'innerHTML',

'615706OhnLTV',

'Correct!',

'getElementById',

'./ZoRd23o0wd',

'charCodeAt'

];

const _0x1125 = function (_0xe99bac, _0x38edc1) {

_0xe99bac = _0xe99bac - 172;

let _0x2f653e = _0x2f65[_0xe99bac];

return _0x2f653e;

};

(function (_0x4bee5a, _0x2f153e) {

const _0x48cd05 = _0x1125;

while (!![]) {

try {

const _0x1ca14e = parseInt(_0x48cd05(183)) + parseInt(_0x48cd05(176)) + - parseInt(_0x48cd05(192)) * parseInt(_0x48cd05(189)) + - parseInt(_0x48cd05(172)) + - parseInt(_0x48cd05(179)) + parseInt(_0x48cd05(181)) * parseInt(_0x48cd05(177)) + - parseInt(_0x48cd05(190));

if (_0x1ca14e === _0x2f153e) break;

else _0x4bee5a['push'](_0x4bee5a['shift']());

} catch (_0x39e004) {

_0x4bee5a['push'](_0x4bee5a['shift']());

}

}

}(_0x2f65, 373983));

let exports;

(async() =>{

const _0x2ff3c6 = _0x1125;

let _0x5a83eb = await fetch(_0x2ff3c6(186)),

_0x304d04 = await WebAssembly[_0x2ff3c6(191)](await _0x5a83eb[_0x2ff3c6(180)]()),

_0x5835e7 = _0x304d04[_0x2ff3c6(188)];

exports = _0x5835e7['exports'];

}) ();

function onButtonPress() {

const _0x2579ee = _0x1125;

let _0x39e007 = document[_0x2579ee(185)]('input') ['value'];

for (let _0x45a858 = 0; _0x45a858 < _0x39e007[_0x2579ee(175)]; _0x45a858++) {

exports[_0x2579ee(178)](_0x39e007[_0x2579ee(187)](_0x45a858), _0x45a858);

}

exports[_0x2579ee(178)](0, _0x39e007[_0x2579ee(175)]),

exports[_0x2579ee(173)]() == 1 ? document[_0x2579ee(185)](_0x2579ee(174)) [_0x2579ee(182)] = _0x2579ee(184) : document[_0x2579ee(185)](_0x2579ee(174)) ['innerHTML'] = 'Incorrect!';

}

I downloaded the JS source code, and then de-obfuscated the source code by hand, with the help of the debugger to understand what each part did. Eventually, I was able to get it down to something comprehensible:

let exports;

(async () => {

let _0x5a83eb = await fetch('./ZoRd23o0wd'),

_0x304d04 = await WebAssembly.instantiate(await _0x5a83eb.arrayBuffer()),

_0x5835e7 = _0x304d04.instance;

exports = _0x5835e7.exports;

})();

function onButtonPress() {

let _0x39e007 = document.getElementById('input')['value'];

for (let i = 0; i < _0x39e007.length; i++) {

exports.copy_char(_0x39e007.charCodeAt(i), i);

}

exports.copy_char(0, _0x39e007.length),

exports.check_flag() == 1 ? document.getElementById("result").innerHTML = "Correct!" : document.getElementById("result")['innerHTML'] = 'Incorrect!';

}

As you can see, the code feeds the input into some WebAssembly (WASM) instance via copy_char, and then calls check_flag within the WASM instance. The WASM instance returns 1 if it is indeed the flag, otherwise it returns some other value. Therefore, we must inspect the WASM code to solve this challenge.

Inspecting the WASM

I downloaded the WASM file, and ran the wasm2wat command (in the WebAssembly Binary Toolkit) to make the assembly code human readable. Additionally, I made my own version of the challenge webpage locally, replacing the minified JS with my de-obfuscated version and then hosting it locally with SimpleHttpServer (for some reason fetch does not work on local files due to CORS, so I have to host a server)

Unfortunately, after converting to human-readable form, it is still practically incomprehensible. The check_flag function nears 800 assembly instructions, and at that rate it’s very hard to understand what that function does as a whole. I decided to start from the end of the function and work backwards, to see what conditions would make the return value 1:

i32.const 0

local.set 152

i32.const 1072

local.set 153

i32.const 1024

local.set 154

local.get 154

local.get 153

call 1

local.set 155

local.get 155

local.set 156

local.get 152

local.set 157

local.get 156

local.get 157

i32.ne

local.set 158

i32.const -1

local.set 159

local.get 158

local.get 159

i32.xor

local.set 160

i32.const 1

local.set 161

local.get 160

local.get 161

i32.and

local.set 162

i32.const 16

local.set 163

local.get 2

local.get 163

i32.add

local.set 164

local.get 164

global.set 0

local.get 162

One important thing to note, is that call 1 calls function 1, which is labelled in the export section as the strcmp function, which takes in two integers and returns an integer. With this, we can make an educated guess and assume that the two parameters are offsets/memory addresses from which to extract the strings, and the integer is the value outputted by the string comparison (similar to how string comparison works in Java and C).

Using some boolean math and that piece of information, it becomes apparent what this block of code does: it only returns 1 if the two strings at memory addresses 1024 and 1072 match. This raises a pretty pressing question: what exactly is at those memory addresses? And where/what is this memory anyway?

It turns out, whenever we initialize a WASM instance, it creates an ArrayBuffer and uses it as its memory when executing instructions. The address locations 1024 and 1072 are defined in the context of this ArrayBuffer - is it possible to read this memory to maybe get more clues?

Inspecting the Memory

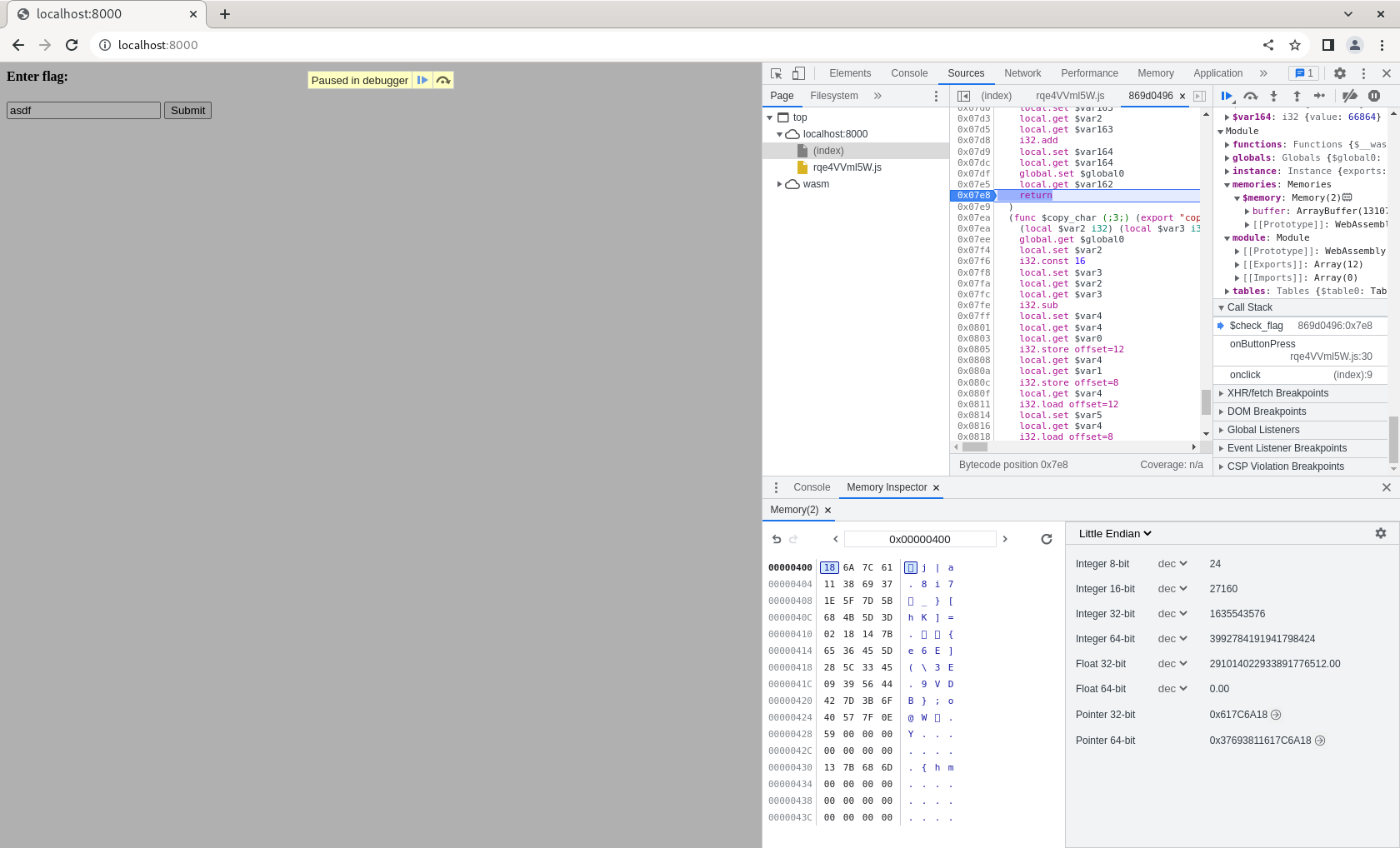

Turns out, it is possible! Chrome’s DevTools allow us to inspect the memory contents of a WASM instance via the Memory Inspector. Since I was using Firefox, I quickly installed Chromium on my laptop, set some breakpoints in the WASM file, and started peeking at the memory inside, particularly at the addresses mentioned:

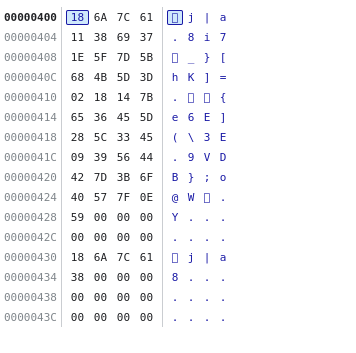

One observation to make, is that the string at 1072 seems to be the same size of the input string. While it is not equivalent to the input string, it is clear that the check_flag function generates some sort of “checksum” somehow, and compares it to the string at 1024, which is the “reference” string. It is now useful to note that the “reference” string is part of the data section of the WASM file:

(data (;0;) (i32.const 1024) "\18j|a\118i7\1e_}[hK]=\02\18\14{e6E](\5c3E\099VDB};o@W\7f\0eY\00\00"))

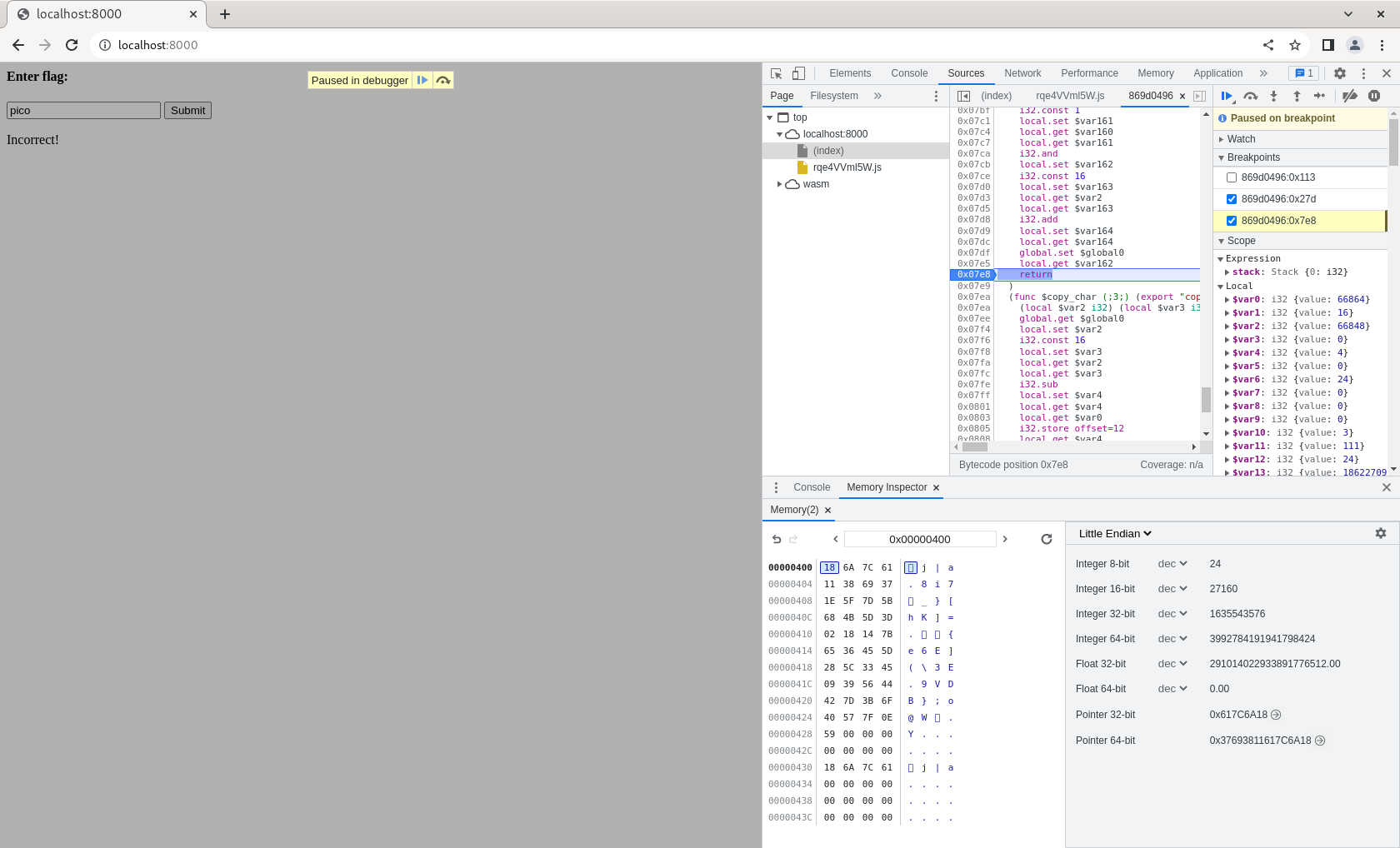

Since it seems to have some sort of character-by-character mapping, it seems plausible that putting in the first few characters of the “correct” answer will yield a string that matches the reference string, for those first few characters. Since we know that all flags are of the form picoCTF{...}, let us guess with pico first:

Wow! It seems as though our hypothesis is correct! The first four characters of the “checksum” generated by check_flag do match the “reference” check_sum. Let us confirm our hypothesis by trying picoC instead:

Hm. It seems as though it doesn’t really match - for some reason the 8 is in the wrong place. Surely the pico match couldn’t have been a coincidence? I investigated further by starting from a blank string and systematically adding extra characters. Note that I had to refresh the page before doing this, because the program does not wipe all the memory addresses from 1072 onwards for every iteration of check_flag we do - it only overwrites the addresses for as long as the input is.

It seems as though our initial hypothesis is partially correct - it does calculbate the checksum from the input character-by-character, but it also seems to perform some sort of swapping for adjacent pairs of characters.

Final Attack

After I have gathered enough information, I can finally strike the final blow to this challenge. I just have to brute-force each character pair of the flag, until I get the full flag. It may seem that we have an annoying corner case to deal with since the reference string has an odd number of characters (43), but luckily we don’t actually have that corner case to deal with since the last character is a null char (meaning we can ignore it). Also since JS lets us read from the WASM’s instance memory directly, we don’t actually have to extract the code from the check_flag function and put in a separate function that returns the checksum string. After some fiddling around, I was able to come up with this cracking program:

// this is the string found in the data section of the WASM file, which it checks the flag against

const correct_answer = "\x18j|a\x118i7\x1e_}[hK]=\x02\x18\x14{e6E](\x5c3E\x099VDB};o@W\x7f\x0eY\x00\x00";

let exports;

let view;

let _0x5a83eb;

let _0x304d04;

let _0x5835e7;

async function scramble(s) {

for (let i = 0; i < s.length; i++) {

exports.copy_char(s.charCodeAt(i), i);

}

exports.copy_char(0, s.length);

exports.check_flag();

// Create data view of memory buffer

view = new Int8Array(_0x5835e7.exports.memory.buffer);

// Extract the stuff starting from 1072, for the length of our string) and return it

return new TextDecoder().decode(view.slice(1072, 1072 + s.length));

}

function isPrefix(pre, s) {

if (pre.length > s.length) return false;

for (var i = 0; i < pre.length; i++) {

if (pre[i] !== s[i]) return false;

}

return true;

}

(async function() {

_0x5a83eb = await fetch('./ZoRd23o0wd'),

_0x304d04 = await WebAssembly.instantiate(await _0x5a83eb.arrayBuffer()),

_0x5835e7 = _0x304d04.instance;

exports = _0x5835e7.exports;

var s = "";

while (s.length < correct_answer.length - 1) {

outerfor: for (var i = 0xFF; i > -1; i--) {

for (var j = 0xFF; j > -1; j--) {

var charPair = String.fromCharCode(i) + String.fromCharCode(j);

s1 = s + charPair;

if (isPrefix(await scramble(s1), correct_answer)) {

s = s1;

console.log(s);

break outerfor;

}

}

}

}

document.getElementById("flag").innerText = s;

})();

// brute-force, advancing two characters at a time

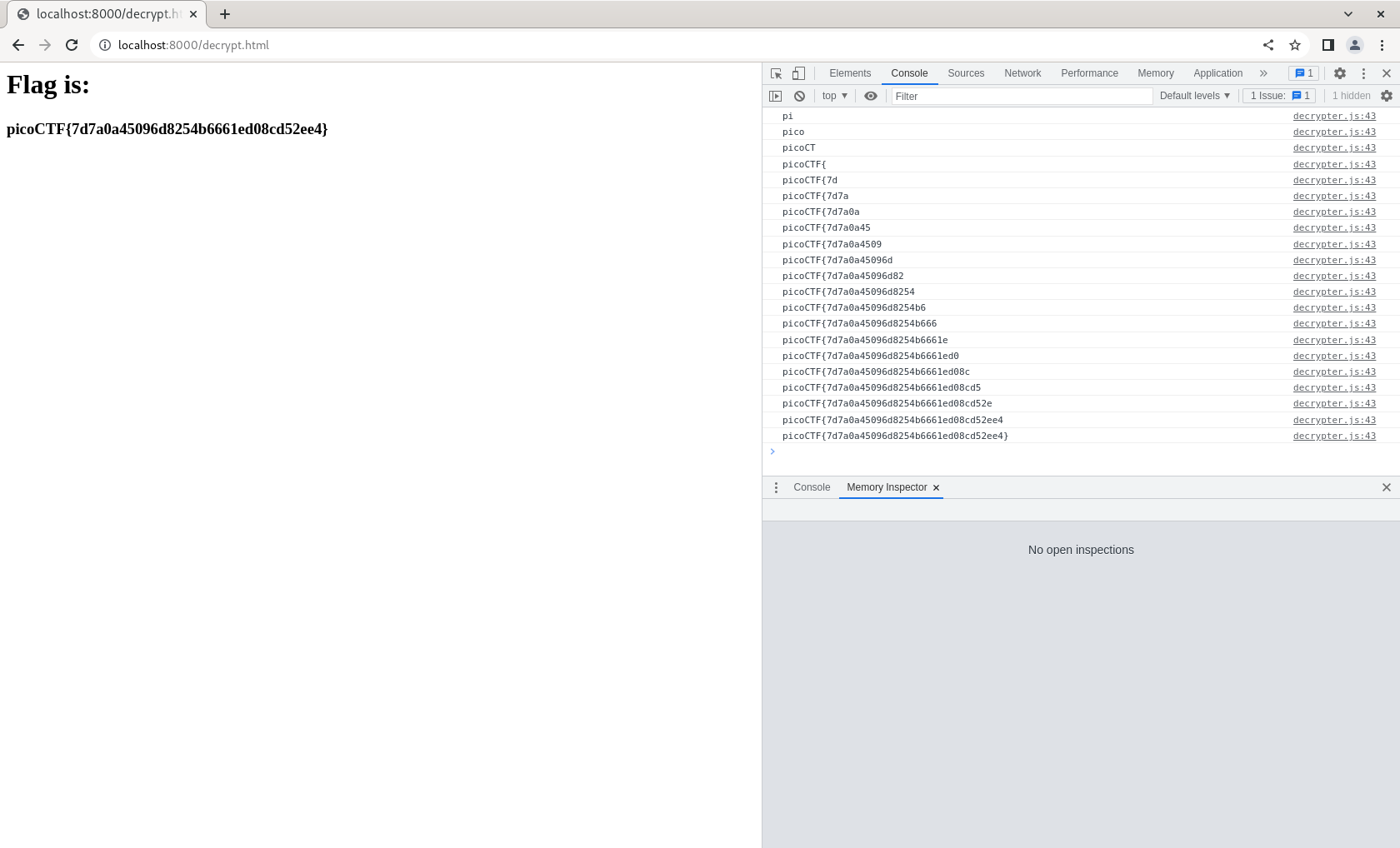

Here’s the companion HTML file, for reference:

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<script src="decrypter.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Flag is:</h1>

<h3 id="flag"></h3>

</body>

</html>

And with that, I found the flag and solved the problem!

Other Solutions?

As I said before, after I found the flag to this challenge, I looked the challenge up online to see what ideas others had come up with. One person used the same approach I did (right down to the memory inspector in Chrome’s DevTools and the two-character attack), but there was another person who did it the “obvious” way. They manually decompiled the WASM code to a programming language of their choice, and then manually reversed the check_flag function of the program from bottom-to-top, and got their program to solve the flag this way.

I initially considered this approach, but after looking at the length of the check_flag method I decided against it. As they point out, it is a foolproof but tedious process, and in their case it took them 9 hours for them to solve it this way!

Conclusion

I think this challenge is emblematic of how CTFs “work”. They are not designed as ultra-tedious trivial programming exercises, rather they are intended to be solved with a combination of background knowledge, Google-fu and experimental guessing.

All-in-all, I found the process pretty rewarding. I learned a whole lot during the process - I learned a completely new dev tool (Memory Inspector), learned how to instantiate a local server, and learned a massive amount about WASM (which I previously knew nothing about).

Needless to say, I will be back for more :)